|

||||

|

|

Alex I Askaroff

Alex has spent a lifetime in the sewing industry

and is considered one of the foremost experts of pioneering machines and

their inventors. He has written extensively for trade magazines, radio,

television, books and publications world wide. Over the last two decades

Alex has been painstakingly building this website to encourage

enthusiasts around around the Globe.

See the sewing machine guru, Alex Askaroff on Youtube: Most of us know the name Singer but few are aware of his amazing life story, his rags to riches journey from a little runaway to one of the richest men of his age. The story of Isaac Merritt Singer will blow your mind, his wives and lovers his castles and palaces all built on the back of one of the greatest inventions of the 19th century. For the first time the most complete story of a forgotten giant is brought to you by Alex Askaroff. |

|||

|

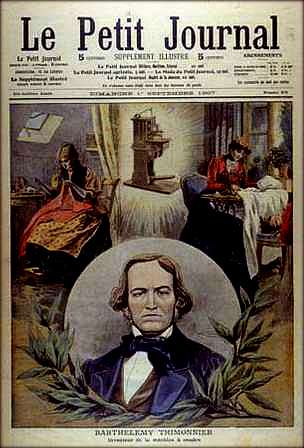

The Tailor of Amplepuis By far the most famous name in the history of the sewing machine (in France) is Barthélemy Thimonnier. Barthélemy Thimonnier, sometimes spelt Chimonnier, is possibly responsible for the first real or practical sewing machine in the history of the world. Calm down, calm down. I only said possibly! You will have to read my full history of the invention of the sewing machine to see how Barthélemy Thimonnier fits into the whole picture of sewing machine development. Although his invention had little impact on the evolution of the sewing machine it was a fascinating piece of kit. Certainly the first factory in the world using sewing machines was because of this great man. You could also say that he was the first person to mass produce (in limited numbers) sewing machines. His story is a wonderful struggle of invention and failure. Let us have a closer look at the first French sewing machine and the fascinating tale of 'The Tailor of Amplepuis', Barthélemy Thimonnier. His Story Barthelemy Thimonnier 1793 - 1857

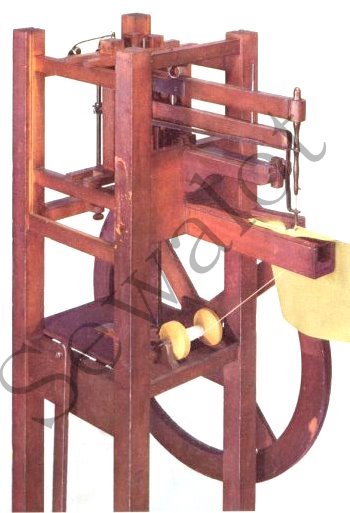

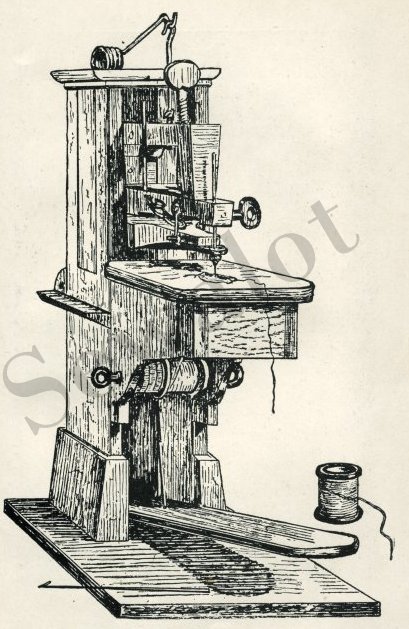

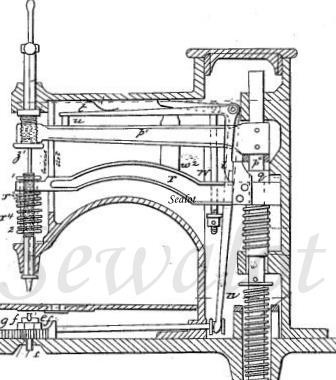

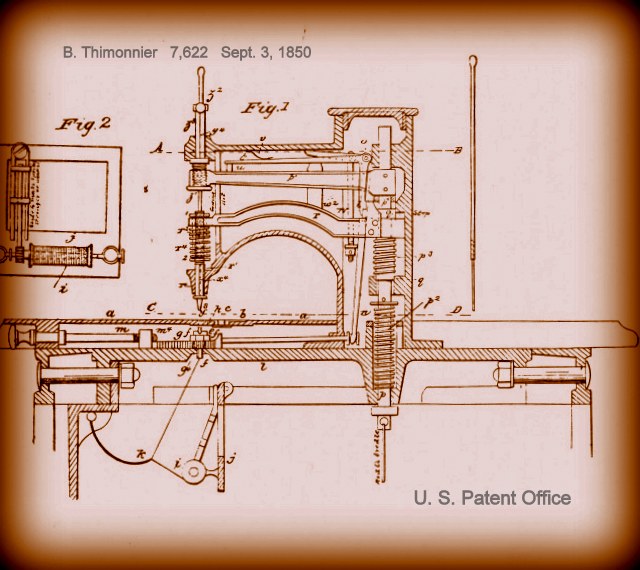

Barthélemy Thimonnier was born on August 19, 1793 in L'Arbresle, Rhône. Barthélemy Thimonnier was the oldest son of seven children. He studied tailoring for a while in Lyon. Barthélemy married Jeanne Marie Bonnassieux and within a few years the happy couple had three children. Tragedy struck and his young wife died, possibly in childbirth. Heartbroken Barthélemy had to leave his children with his mother and leave to find work. Barthélemy travelled around as a tailor finding work where he could. This was a surprisingly popular industry. You have to think that at the time all clothes were made by hand. A skilled tailor was in demand and he could pretty much set up shop anywhere making garments for local dignitaries as he travelled around, all the time sending money home to his mother to support his children. In 1822, while working in Panissieres he met, fell in love and married Magdeleine Varinier. A year or so later around 1824-25 he settled just outside Saint-Étienne near Paris and set up a tailoring business. Tailors worked hard and were paid poorly. As Barthélemy Thimonnier sewed away each day his inventive mind was hard at work trying to figure out how to make a machine do the low-paid work of the tailor. Barthélemy was no engineer but he had struck upon the idea of mechanising a crochet hook used by so many seamstresses and knitters. If he could work out a way of making a machine that pulled the thread through fabric using a hooked needle he could sew faster than any hand-stitcher and earn more money. Bart formed a friendship with Auguste Ferrand who had some engineering skills and was working as a teacher at a local mining academy. After years of trial-and-error the two of them formed a machine out of wood and metal that actually did help to stitch fabric. It was large and complex with roughly engineered gearing but it actually worked slightly faster than sewing by hand. 17 July 1830 Barthélemy Thimonnier & Auguste Ferrand By 1829, the two had cobbled together the very first French sewing machine. By June of 1830 the pair had gone into partnership. The patent for their machine was issued on 17 July 1830. The first real practical sewing machine that we know of was born although in reality it was sort of loop-catcher, crochet machine, rather than the stitch that we recognise today. Barthélemy Thimonnier sewing machine Barthélemy Thimonnier's, first, mainly wooden sewing machine. The thread is below the table and was caught by the barbed needle and pulled through the work. The machines were nicknamed 'arm breakers' or 'leg crackers' as they were so hard to work. Note the barbed needle laying on the base of the machine. You can see how it would snag the material as it is pulled through which really was his big problem. Barthélemy Thimonnier (I'm going to call him Bart now as it makes my head hurt spelling his name) took out a further patent for a barbed needle to be used in his sewing machine. Smaller versions of his barbed needles are still used today in embellishing and other sewing machines such as Cornely, Singer, Bonnaz and more. There are many new machines today that are based on his principle of under-bed threading. Because you can use much thicker threads his design is actually ideal for free motion pattern quilters, embroidery, and fabric artists.

How does the

Thimonnier

sewing machine work?

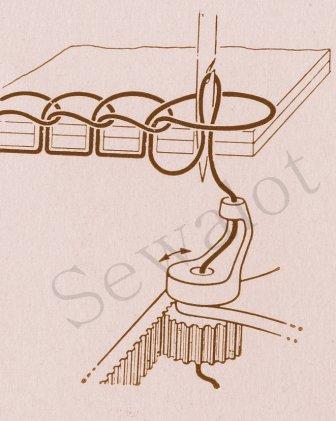

This is tricky but stay with me as it is worth learning how the first French sewing machine worked. It is all done with one thread, fed from below the machine. Imagine a standard chain stitch but in reverse, thread, fed, from the bottom of the machine rather than above. An open-gapped barbed needle, supported by a wooden frame (above the work) is thrust downward through the fabric by the operator (usually seated). This is done by pressing on a wooden plate below the machine at floor level. Barthélemy Thimonnier needle

The needle catches the thread held by a spiral looper underneath and lifts it upwards through the fabric. The operator then moves the work along and stops (this was a major drawback that was later perfected by Wilson's four-motion-feed). The operator then presses on the foot plate again thrusting the needle (still threaded) back downward through the work where the spiral looper twists (via timed gears) once again, grabbing the thread, looping it into the preceding piece of thread. This creates a basic chain stitch BUT with the loops of stitching showing on top of the work and the straight row of single stitches underneath. You can see this basic movement on many chain stitch machines, just the other way around, which is why it is so useful for embroidery work and still popular today. It was really when electricity added speed to Bart's tambour stitch that it came in to its own as the faster the barbed needle moves the less time it has to snag the fabric. Singer model 114W

The sewing machine that Barthélemy Thimonnier & Auguste Ferrand made was primarily of wood with metal springs and other working parts. It worked by producing a simple chain stitch, or as they called it on their patent tambour stitch, you know the sort of stitch you find across the top of potato sacks. Original

woodcut of the 1833 Thimonnier sewing machine or tambour machine. The first contract for mass production Hand sewing did not produce equal lengths of stitches. Only the most proficient of seamstresses could make the stitching appear uniform. Neither did Bart's machine! But it worked well enough for Barthélemy Thimonnier & Auguste Ferrand to gain a contract to make uniforms for the French army, undercutting all other quotes. This was true mass production of sewing for the first time in history. Operators became highly skilled at edging the seams forward in equal lengths, by using their thumbs wedged at the side of the wooden platform as they moved the work along, after each press of the pedal. They would immediately stop if the fabric was caught by the special barbed needle (instead of passing cleanly through it) and wipe away the caught fabric before continuing. This mass production meant that sewing the uniforms by machine worked out at one third the cost of hand sewn garments. Bart could cut the cost of the uniforms to the military by half and still make more money than before. This profit was immediately put into more machines for his workshop. Improvements were made with each new machine. Before long Barthélemy Thimonnier & Auguste Ferrand were sewing away with dozens of machines, taking work from the hungry tailors of Paris. The first sewing machine factory in the world was doing well. BUT we all know what Frenchmen are like when their blood is up. Remember at this time Madame Guillotine was still warm from their revolution. On the 20 January 1831 a crowd or angry out-of-work tailors ransacked the Rue de Sèvres factory. At first they threw garlic at the machines but to their amazement they bounced off! They then decided to have a booze up and torch Bart’s workshop properly. A crowd watched on as the shouting tailors piled all the wooden sewing machines up outside Bart's workshop and burnt them before turning on the workshop as well. They probably danced around the fire singing Vive La France or something like that. Poor old Bart narrowly escaped being tossed onto the fire himself and headed for the hills, his business in flames. Sabotage Interestingly some say that the word sabotage comes from the industrial revolution. French workers wore heavy wooden clogs known as 'sabots' to keep their feet above the dirt. They would often use them to jam the machinery in the looms. No one could make you take your shoes off so you could go anywhere with them and use them as a hidden weapon of destruction. See how interesting this page is! Now back to Bart... At some point Auguste Ferrand disappears from our story. Unperturbed, and with that usual French resilience, Barthélemy Thimonnier started all over again with an even better model. The renamed 'Embroidery Machine' was now capable of sewing 200 stitches per minute, seven times faster than a tailor by hand! I would love to see one of his machines in action as I believe that his mechanism was doomed to failure due to his needle design (which may snag as many threads in the fabric as it made) and having to tug the work along by hand. The faster the machine moved the more thread snags it would make... A later patent managed 300 stitches per minute. By 1832, Barthélemy Thimonnier was back in Amplepuis with an improved version of his machine. More patents followed in 1841, 1845, 1847 and 1848. Here is one of only two original machines still known to exist. I snapped this picture with kind permission of Ray Rushton who has the incredible London Sewing Machine Museum. Ray paid £50,000 for this unique piece of sewing history which surfaced in South America. The London Sewing Machine Museum is open on the first Saturday of each month and is free. Back to 'trouble at the factory'... The sneaky French tailors kept an eye on old Bart and as soon as they found out what he was doing they set about the poor fellow again, this time with far more powerful weapons, strings of onions! Barthélemy Thimonnier fled to England (just like the many aristocrats that had feared for their lives during the French Revolution years earlier). Where was the Scarlet Pimpernel when he was needed eh! It is unfortunate that the French, at that time, did not see the potential of the sewing machine. It made people like Isaac Singer and Elias Howe fabulously wealthy. It also saw the start of true mass production long before the likes of Henry Ford, and provided millions of jobs around the world. There is no doubt in my mind that had the French embraced this new technology earlier they would have benefitted as a nation beyond any imagination. Jean-Marie Magnin Many years later an engineer from Villefranche-sur-saone, near Lyon, named Magnin, who was the son of a lawyer took a keen interested in the works of Thimonnier (for whom money was always lacking). In 1845, under the name of Thimonier et Magnin, they renewed Thimonnier’s original patent of 1830 and organised the first French manufacture of machines for sewing in Villefranche-sur-saone. This manufacturing process allowed our inventor to put in action certain refinements of which he had long dreamed. The completed machines were able to make a reliable 200 stitches per minute and were sold at 50 francs a piece. On the 11th of August 1845 The Journal of Villefranche presented the machine to the public. The audience were impressed with its qualities but 50 francs was a kings ransom, so few orders followed. Thimonnier went on to patent his improved model in America in 1850. In October 1847 Barthélemy Thimonnier and Jean-Marie Magnin patented more improvements to their embroidery sewing machine. A faster type of Tambour stitch machine followed. In England he tied up with Phillip May of London & Manchester to secure his patent. Barthélemy Thimonnier patent, England, 8 February 1848 Unfortunately Barthélemy Thimonnier stuck with his old ideas of hooking and pulling threads rather than improve his type of unreliable stitch and adding a feed mechanism. The stitch came undone easily and had to be sealed at each end with candle wax. Also it was easy for the machine to miss stitches and once a stitch was missed the whole seam could unravel. Basically the design was flawed (unlike the Willcox & Gibbs chain stitch which had overcome all the problems associated with it). Barthélemy Thimonnier was still going strong with his flawed machine and in 1850 he applied for American patents in the hope of securing lucrative business in the largest democracy in the world. However his design was now terribly outdated and overtaken by Elias Howe and others with their vastly better lock stitch machines. The Final Straw In England he sold some of his patents to a Manchester firm. Jean-Marie Magnin entered their machine in the 1851 Crystal Palace Great Exhibition in London. Unfortunately his demonstration machine was held up and never made it to the show. He pleaded with the judges but rules were rules and the machine was excluded from the competition. This was the last resort for Jean-Marie Magnin who returned the machine to Barthélemy Thimonnier and in a fury returned to France. their partnership was over. Barthélemy Thimonnier had to be one of the unluckiest entrepreneurs/inventors that I have ever come across. By the late 1850's he should have been far richer than Isaac Singer and Elias Howe combined. Barthélemy Thimonnier's real problem was similar to that of Elias Howe, he could not sell his machine well. A week with a double glazing or insurance salesman would have worked wonders for him. One of Bart's real problems was they way he tried to promote his machine, he hit the domestic market instead of looking at the factories like Isaac Singer had. It was the factories that could afford his machine. He also became aggressive towards any poor publicity, blaming everyone else... "The tailor or man of work who 'opposes' my machine is like the child that revolts against his nurse. It makes no sense to me why my inventions should be attacked." B T 1850 Hummn! Me thinks he needs a little lesson in how to talk to people. Thimonnier knew that people were having trouble trying to operate his difficult machine and wrote some improved instructions which even included how to make an assortment of different barbed needles.

1855 World fair This helped a little and after perseverance at the 1855 World Fair in Paris Barthélemy Thimonnier won the First class or Gold Medal. I am not sure if that was the French pampering their own as by now many far better machines were being exhibited and sold. This was a bit of French politics trying to show the world that it was a Frenchman, one Barthélemy Thimonnier, who had actually invented the first practical sewing machine and the first country to mass produce a sewing machine. In reality the machine was not as good as the foreign competitors at the show. The Tambour Sewing Machine

United

States Patent Office As much as he tried poor old Barthélemy Thimonnier never regained his former success and although he had made one of the first reasonable machines capable of a type of sewing in the entire history of the world it did not stop the old tailor ending up broke. Death of The Tailor of Amplepuis Just two years after his success at the Paris show he died in poverty, never gaining from his amazing invention. Barthélemy Thimonnier died on 5 July (or possibly August depending on what research you read) 1857 at a good age (for the time anyway, he was 64) back in Amplepuis. Barthélemy Thimonnier's legacy Amazingly, in some form or another the Thimonnier name was associated with sewing machines (mainly sold in France) right up until the 1950's. His son Etienne Thimonnier kept an original working model of his father's machine for over 30 years, a memento of his father's efforts. In 1871 Etienne opened a small shop selling sewing machines and bicycles which he brought in from various countries. In 1883 Etienne Thimonnier was granted an US patent, 287,592 for a sewing machine which they had successfully patented around Europe.

Le Petit Journal 1907 The company formed by Etienne Thimonnier (and possible partners Fils & Vernas), carried on diversifying and growing. Jump forward a few World Wars and by the 1980's no more sewing machines were sold by the company which by then were concentrating on plastic packaging and bag closing equipment. Barthélemy Thimonnier would have been very proud of the fact that his name will be immortalised for being one of the first people in the history of the world to invent a working and usable sewing machine and setting up the first mass-production workshops using sewing machines. Musée Barthélemy Thimonnier There is a Barthélemy Thimonnier museum in Amplepuis housed in an old church, Musée Barthélemy Thimonnier. In the museum is one of Bart's replica machines. In Lyon in 1931 at Place de L'Abondance a statue of the great inventor was erected. In 1955 the French Postal Service ran a series of stamps depicting great French inventors, Barthélemy Thimonnier was on the 10 franc stamp but for some reason they managed to put his wrong date of death (stating 1859 rather than 1857). Most of us know the name Singer but few are aware of his amazing life story, his rags to riches journey from a little runaway to one of the richest men of his age. The story of Isaac Merritt Singer will blow your mind, his wives and lovers his castles and palaces all built on the back of one of the greatest inventions of the 19th century. For the first time the most complete story of a forgotten giant is brought to you by Alex Askaroff.

News Flash! Alex's books are now all available to download or buy as paperback on Amazon worldwide.

"This

may just be the best book I've ever read."

"My five grandchildren are

reading this book aloud to each other from my Kindle every Sunday.

The way it's written you can just imagine walking

beside him seeing the things he does. News Flash! Alex's books are now all available to download or buy as paperback on Amazon worldwide. And so my friends Alex Askaroff, the sewing machine guru, brings to an end his musings on the great French inventor. WAIT! their is still a little more...

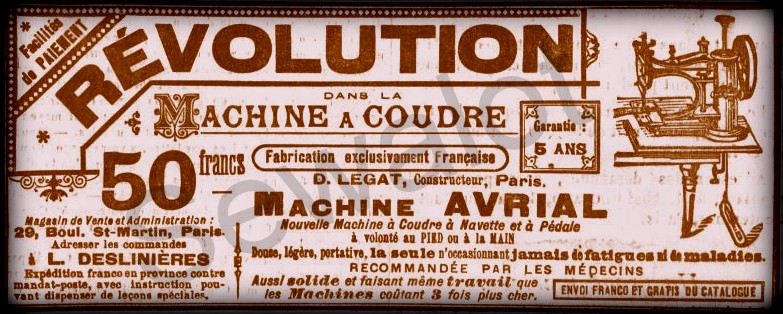

There have been several other

notable French sewing machines including Legat, Peugeot and my personal

favourite

Hurtu sewing machines. I have a whole page on

Hurtu sewing machines and it is well worth your perusal.

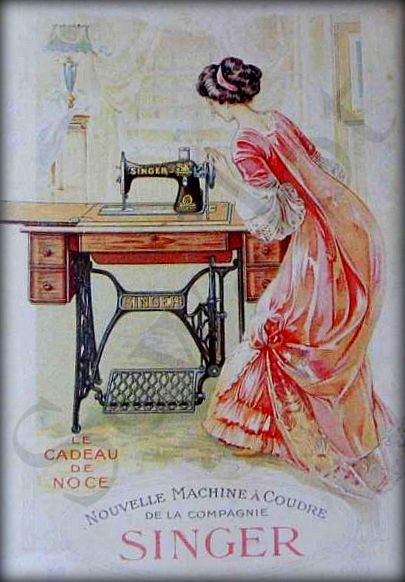

Legat Sewing Machine, Paris. Singer Sewing Machines

|

||||

|

Fancy a funny FREE read: Ena Wilf & The One-Armed Machinist

See the sewing machine guru Alex Askaroff on You Tube... http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3mJYS44Vc8c&list=UL

Hi Alex

Alex, Alex, that was some great research. No wonder they call you the sewing machine guru. Thank you from Alberta, Canada, M.S.P

Well that's it, I do hope you enjoyed my work. I have spent a lifetime collecting, researching and writing these pages and I love to hear from people so drop me a line and let me know what you thought: alexsussex@aol.com. Also if you have any information to add I would love to put it on my site.

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

CONTACT: alexsussex@aol.com Copyright ©

As a

new collector I have found your site

has increased my knowledge in

a short time to a degree

that I couldn't have

imagined. |

||||